Venomoids: An Overview

from

Jeff Miller

on

March 29, 2001

View comments about this article!

The following article is for information purposes only and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Southeastern Hot Herp Society.

†

Anyone who has had any experience with venomous reptiles has had a chance to engage the thought of keeping a venomous snake that has no venom. A "venomoid" is a venomous snake that has been subjected to a surgical procedure aimed to prohibit the use of its inherent venomous capabilities. This would seem to open many doors for those who have enjoyed a fascination with venomous species of snake, but are unwilling to risk keeping one in their home. Many purists absolutely despise the idea, while others embrace venomoids as a viable option and alternative to keeping potentially deadly animals in the home, or otherwise close proximity to human beings. Either way, the subject of venomoids has become a huge debate within the venomous community, and it is a subject that should be addressed. They are not going to go away.

In this article, I will attempt to gather and present as many actual facts as possible in relation to the subject of venomoids, considering only the species most commonly devenomized (not rear-fanged or other more obscure species), and discuss the controversial status of the subject among hot-herp keepers from all backgrounds. I have been told writing such an article would be a daring endeavor considering the subject matter and the intended readership. But as an experienced keeper of several species of venomous snakes myself, I believe I have become appropriately acclimated to safe handling of hot subjects. I must make it clear that I am not a professional by any means, and observations made and conclusions I have come to are from my own amateur study, discussion with more educated folks, and personal observation as an amateur herpetologist.

Since humans have been keeping animals in captivity, they have chosen to alter the animals in some way to fit their needs. Whether it is castration, cropping ears, de-horning, branding, breeding, milking, consuming, etc, humans have felt the need to use animals for whatever need there may be and alter them appropriately, and we will continue to do so. In captivity, venomous snakes are collected, bred, displayed, exhibited, bought, sold, traded, and exploited. Interestingly, venomoid snakes sold in the herp market carry a much higher price tag than unaltered snakes of the same species, despite actually becoming less characteristic of that species after having been altered. Some enthusiasts figure it to be a great advantage to be able to observe all the beauty and behavior of a venomous species, without being subject to the obvious risks associated with keeping them in captivity. This brings to question the option of venomoids and along with that many aspects, including historical significance, procedures, the post-operative health and well being of the animals, reasons for creating venomoids, venomoids in the herp trade, and even the ethics involved with altering a venomous snake in the first place.

Historically, various versions of venomoids have been encountered in many parts of the world. In India, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, venomous snakes have been in use for centuries as the center of entertainment on streets and in markets, displayed in demonstrations to show effectiveness of certain home-remedy snakebite treatments or immunity, and simply to spotlight seemingly supernatural power or skill in escaping bites from such species while handling them with bare hands. Ceremonies and religious re-enactment also found uses for venomous snakes, even in areas of Southwest and Southeast United States where Native Americans altered rattlesnakes for use in ceremonial displays. While many of these snakes were left in a completely natural state and merely handled frequently until they were more tolerant of human interaction, most were made to be less of a threat to their human captors through crude means. Methods of alteration have included simply breaking and removing the fangs from snakes to actually sewing the mouths shut with a needle and thread. Needless to say, most altered snakes used in such displays were considered disposable as they were no longer able to feed and once they no longer served their purpose, they were discarded and replaced.

The modern captive reptile hobby involves a variety of different people from different backgrounds, and thus a few different types of "enthusiasts". Scientists, naturalists, biologists, herpetologists, herpetoculturists, zookeepers, educators, a wide-ranging skill variance of hobbyists, animal dealers, and the same entertainers who use dangerous animals as display novelties to awe the public make up the often-segregated community of modern reptile enthusiasts. Exhibitionists still have their place in many cultures, including ours, and the thrill of performing dangerous feats in the public eye is still very popular and still employs the use of venomous snakes, both altered and not.

There is much debate and opinion concerning the devenomization of captive venomous snakes among the different factions of enthusiasts, and for obvious reasons. There is also debate on the true legitimacy of venomoid snakes in the hobby at all, or the ethics involved with actually subjecting a perfectly healthy venomous snake to such a procedure. Venomoid supporters often cite the aspect of safety as a legitimate reason to "fix" a snake. In the opinion of some, if one is going to keep a potentially deadly snake in captivity, in the home, or on public display, then the liability alone allegedly calls for a "safer" version of a venomous species. Many keepers want to enjoy the uniqueness and species-specific behaviors and features of a venomous species without the risk of being envenomated. Many keepers regularly work with their snakes in educational programs in close proximity to children or others, and feel that there is no reason to have any such risk involved in education and in such an environment prefer to work with venomoids. The operators may feel the educational value of their program would be lacking without including venomous species live and in person, able to demonstrate threat display and defensive behavior without endangering the presenter or the audience.

Commonly, those who seek venomoids are those of little experience, who feel that the best way to learn about keeping dangerous snakes is to keep a dangerous snake that has less "bite". Or maybe they are simply afraid of getting bitten at all. Sometimes, even more experienced keepers justify the option because the threat has been a noticeable hindrance to their husbandry practices. Venomous snakes require special and meticulous care both in cleanliness of the enclosure, and also to accommodate the obvious risk in a safe manner. Cleaning cages can require quite a bit of thought and preparation in order to do so safely. Keepers who have not been able to invest in expensive caging systems may not have utilized benefits such as trap boxes, or safe chambers for transferring a snake from one container to another. An episode of moving a large venomous snake from one spot to another may be enough of an ordeal to encourage procrastination of cleaning duties, thus one more reason to have a less-threatening snake around.

Probably the most common and controversial reason keepers opt for venomoid snakes is because they want to be able to free-handle the snakes without risk of serious injury. Be it out of the simple fascination of close interaction with a normally inaccessible species, or for the more macho reason of impressing friends, the thrill is undeniable and tempting to many. Quite possibly, venomoids have achieved their current popularity in the hobby for this attraction alone. Still risky, as only the snakeís venom apparatus has been inhibited and the fangs are still quite operational and fully intact, the activity is often discouraged by most everyone considering the odds of regeneration may still be in question.

At the far end of the same spectrum are the exhibitionists who want to seem impervious to the threat of a venomous snake, and use snakes to impress an audience by offering displays of seemingly dangerous stunts performed without tools or protection of any kind, encouraging the snakes to react instinctively to threatening approach. Some of these stunt persons are purists, and would prefer the threat is real, while others prefer to merely trick the audience at the expense of the snakes. Not only are these show-types abundant in exotic third-world countries, but they enjoy plenty of attention domestically as well, both in the media and in suburban households- basically anywhere someone needs an audience.

Purists who are opponents of the venomoid option have a far less complicated and varied argument. According to the more conventional and conservative of the venomous keeping community, captive venomous snakes deserve to be left alone, unaltered in their anatomy. If a keeper desires a less-dangerous snake in order to escape the risk involved with keeping a snake, they should have a non-venomous species of snake. Experienced keepers of venomous reptiles feel very accomplished in their skill, and the idea of a new or less experienced or less "respectful" keeper housing the same species without having to apply the same advanced level of husbandry and handling is considered an abomination to the whole idea of keeping venomous. Not only do individuals of the purist persuasion consider the devenomization operation inhumane and an unnecessary stressful experience for the snake, but they also deem the transformation unnecessary as an option. They take the stand that if one is to keep venomous snakes, they need to conduct their husbandry practices appropriately, not alter a snake to fit their situation. Or, a phrase used popularly by opponents in venomoid debates is, "If you canít stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen."

In the opinions of the purists, as far as using venomous snakes on display in zoos or in an otherwise educational environment in close proximity to people, we should be required to utilize appropriately secure enclosures as our only option. If this were not an option, then any program would have satisfactory impact displaying only non-venomous reptiles, and merely having photographs of venomous species on display to prevent further liability. Even those more accomplished and skilled handlers could get by demonstrating the proper methods of handling dangerous snakes with sufficient levels of security in front of a present audience. Many prefer such close interaction with the public while displaying venomous snakes because the experience is arguably a richer one for the audience, being a step closer to realism taking over where television specials and Zoological park displays leave off. In these cases, purists contend that liability should only be an issue if proper preparation and precautions have not been taken.

From a biological standpoint, the debate surrounds the subject of venom itself, and the utilization of it by snakes to both secure their pray, and then aid in the digestive process hence. Opponents in the venomoid controversy contend that venomous snakes have their venom for a reason. If they are denied the use of their venom, they surely cannot survive- at least for very long. Many liken the procedure to removing a mammalís saliva glands, and insist that venom is just as important to digestion. On the other hand, venomoid keepers argue that when cared for properly and given only pre-killed prey, healthy venomoids are able to sustain and live to full longevity without any obvious deficiency. This theory stems from experience with a variety of venomoid species, such as elapids, rattlesnakes, and even Old World viperids such as Bitis species, and their proven full recovery and ultimate survival as venomoids. How?

Facts can shed light on this area of controversy. Venom composition is extremely variable among the worldís venomous species, differences ranging by genus, species, environment, range, and habitat. But, the purpose of venom among major groups of snakes is basically the same. Wild venomous snakes use their venom in three major ways. First and foremost, venom is used to secure or immobilize a prey animal. Secondly, certain enzymes in most venom composition aid in the actual digestion of a consumed prey item. For example, when a snake that has hemotoxic qualities in its venom bites a live prey animal, the venom attacks the blood and live tissue, and after being carried throughout the body via the bloodstream, begins the breakdown of many systemic processes. This will immobilize the animal, and also effectively turn its insides into mush, making it a more easily digestible meal. It cannot be proven which action of the venom is actually most important in the mind of the snake, although we can assess that when a venomous snake bites and releases a prey item, the snake will follow instinctively with the intention of consuming a meal. But it is well accepted that most venomous snakes do not strike previously killed prey items with the intent to envenomate them, as the animal is already immobilized. Instinct apparently doesnít suggest that venom is needed every time a snake consumes a meal, or they would also bite dead prey in the same manner. Further, the digestive properties in venom are comprised of many enzymes that break down proteins, and most animals produce these same enzymes. These components, being so commonly produced, must be considered ingredients that partially make up animal venom. This is not because it is needed to aid in the digestive process, but more because the same compounds utilized in digestion are also being used to quickly attack and destroy the systemic integrity of a prey animal, effectively immobilizing it as soon as possible. Venom is not necessarily unique in its chemistry to other actions in a creatureís body, but is utilized as venom because those components are available, being already produced by the body.

To present an analogy, prunes are a natural source of fiber, or essentially a laxative. Human beings are known to consume these to aid their digestive process, particularly in times of irregularity. Because prunes may aid in the digestive process under certain conditions, this is not to suggest that humans need prunes to digest their food successfully. Most human beings are perfectly capable of consuming and digesting food without the aid of certain additives, which may further assist in the process. Or, one could mention the idea of putting a large club sandwich in the blender before eating (drinking) it, so it will be "easier" to digest. So it is with venomous snakes and their venom.

As a side note, many Old World vipers such as gaboons and other Bitis "walk" their fangs along the body of prey animals to help aid in swallowing them. It is suggested that they are injecting venom into the animal as they do so to begin to further digest the food before it is consumed. This is an assumption that is not consistent with the behavior of other viperids and pitvipers, which most often bite once, then seek out and consume the fallen prey apparently not so concerned with pre-digestion. Further, the action of "walking" fangs up a prey itemís body does not necessarily simultaneously employ a response from the venom glands to discharge venom. I have also watched my Hydrodynastes gigas attack and consume rodents in a similar manner that suggests that the snake is intending to soften the meal and indeed initiate possible pre-digestive processes. But given the unique composition of this speciesí venom and saliva, and method of delivery, this seems more appropriate for Hydrodynastes and similar rear-fang species. Also as a related note, it has not proven to be possible to effectively devenomize Hydrodynastes.

In nature, all species of venomous snakes are conditioned to accept and consume carrion. While younger snakes may be primarily stimulated only by live or moving food, feeding stimuli in older snakes overwhelmingly utilizes both the senses of sight and smell and with pitvipers the use of heat-sensitive pits. These snakes can be stimulated into a feeding response using a combination of all these senses, or any of them singly. This fact alone suggests what herp keepers have known for generations: captive snakes can be acclimated to feeding on pre-killed food items. But this still doesnít approach the question of venom and its roll in the process.

As illustrated to me by a more educated buddy of mine:

"Naja contains cytotoxins, which can break down skeletal muscle. Some have more than others, but this would be advantageous for pre-digestion. The species that are stronger in neurotoxicity (i.e., nivea, haje) will have less advantage with pre-digestion than lets say, pallida, mossambica, or nigricollis. Bitis have some hemorrhagic qualities, and can cause some necrosis, but their main targets are cardiovascular, and blood chemistry complications. Crotalus is the one with the best advantage by far. Theyíre heavy with hemorrhagic and myonecrotic qualities (i.e., PLA2, and low mw myotoxins). This genus would rank at the top with (probability of benefits of) pre-digestion based on those facts. Ö now for some logic. First off, the non-vens don't need it (venom). The stomach contains enzymes (i.e., amylase, chymotrypsin, etc.), that can break down the prey just fine. Second point, most of my vens, when fed dead prey, don't inject venom. Why waste it? They'll save it for a more opportune time. It's meant to kill. Last point, look at the mamba complex, they have no enzymes at all, or classical cytotoxins. Necrosis is basically absent, (and) they digest (their prey) just fine." (T.Friede)

Venomous snakes in nature that consume prey they have found already dead are able to digest their meal regardless of a lack of venom just as non-venomous species would. This also supports the observation that captive venomous snakes can survive on a diet of pre-killed food items, and most often do so exclusively in the well-established collections of many experienced keepers. If this were the case, if a snake were somehow void of venom and under captive care, there would be no reason not to expect the snake to thrive on an exclusive diet of pre-killed rodents. Aside from this assessment from a biological standpoint, keepers of venomoid snakes have been actually "testing" this theory for some time, though not under the same controlled conditions science would. Because of the relatively short history of modern venomoid snakes and lack of related study, it is yet impossible to know of any truly long-term detriment to a captive life without venom as a tool to aid in the digestive process. However, all things considered, envenomated prey will take less time to pass through the digestive process than pre-killed, non-envenomated prey, as part of the job has been given already accomplished by the enzymes in the venom, or the animal has been made to be more palatable. This would mean that there could be significant difference in growth rate between venomoids and unaltered snakes. It also may be that temperature plays an integral role in the utilization of venom, and under natural uncontrolled conditions, snakes do not have the benefit of a reliable heat source. If a reptile has recently consumed a meal and does not have the proper temperatures present to effectively digest the matter, this could have serious consequences starting with the loss of that meal. Considering this scenario, venom surely would aid in digestion. If this were the case, under captive and controlled conditions where a consistent heat source is normally available, it would likely allow these species and venomoid versions alike to reliably digest meals regardless. It should be added here for the sake of discussion that non-venomous reptiles must deal with the same natural inconsistencies and variance without venom, and exist successfully regardless, which supports the statement that the primary use of venom in the animal kingdom is to secure food.

The third important use of venom is as a defensive weapon. Very effective in this usage, it is accepted by herpetologists that snakes intend to conserve their venom for securing food, and only attempt to envenomate in defense as a last resort. It is also acceptable to assume a wild snake could indeed lead a full lifetime in its environment never once having to dispense venom in a defensive reaction. If a threat is never encountered, a snake will have no self-preservative use for its venom. Venomous keepers from both sides of the coin agree that the primary objective in safe venomous snake keeping is preventing an accidental envenomation. For obvious reasons, no one wants to get bitten by a venomous snake, captive or wild. If such is the case, we would plan that our captive snakes have no defensive purpose for their venom, and we would also plan to never allow them to use their venom in that manner. Living a captive lifestyle would offer no suitable threat to suggest the use of a snakeís venom to protect itself, therefore invalidating any ability to do so. This does not, however, necessarily validate the removal of this ability.

While these assessments are logical, it is not to suggest legitimacy of venomoids themselves, but to merely clarify the likelihood of a venomoid snake surviving and possibly thriving in a captive environment. Or, it is an attempt to explain why so many venomoids have proven to thrive under captive conditions, despite popular opinion or assumption. We must also keep in mind that the utilization of venom by various species of snakes will vary greatly. Some species may very well rely on venom more consistently for digestion, and other species may require it more for digesting some prey items than others. In these cases, voiding a snake of its venom may have either short or long-term effects on its well being, although this has yet to be proven either way. There are many opportunities for study in this area by academically trained biologists and toxicologists, and while venomoids may never be accepted by the community as a whole, they offer a unique opportunity to study the physiology and subsequent quality of life for a venomous snake that has been devenomized.

†

†

Procedures: For the past several years, many people have ventured into the unknown performing a variety of procedures in the attempt to inhibit a snakeís ability to produce or utilize its venom while keeping it otherwise alive and well for whatever purpose. As mentioned before, these procedures range from relatively crude and simple (yet ultimately ineffective and non-permanent) methods such as removing fangs from the mouths of pitvipers and sewing the mouths of cobras shut with needle and thread, to much more studied and effective surgical procedures performed under controlled, sterile conditions. There is a wide range indeed from one extreme to the other, and it must be stated that no method can be definitively deemed 100% effective in inhibiting a venomous snakeís ability to produce venom, or otherwise succeed an attempt at envenomation. Plus, there are plenty of damaging devenomization attempts that can be deemed downright ineffective and wasteful. That being said, a few operations have been proven to be effective thus far, even to the point that there seems to be no obvious detriment to the health of the snake post-operatively speaking. In the next section, the devenomization methods of one individual are documented in detail. This is not meant to be a faithful representation of a standard by which devenomization procedures are being performed, but more a representation of how one skilled operator conducts these procedures. There currently is no measurement or standard by which to follow, and the general act of devenomizing snakes is not officially condoned by any veterinary institution that I know of. Obviously, I could be mistaken. As a side note, this is by no means intended to be step-by-step instruction. If one were to take these pages and begin operating on snakes based on the information alone, then the lives of those snakes would be put to waste. Also, as I am not a veterinarian or a scientist, I can only relay what I have observed without much commentary to the validity of any part of these procedures. In other words, donít try this at home. The individual performing these procedures has several years of experience and over 400 surgeries under his belt. He also happens to be a professional educator who holds well over 400 herpetological education programs each year, and contends that a high percentage of the surgeries he performs are on animals to be used on display in educational institutions or in his own programs.

Also to be noted is the fact that here, surgeries are NOT performed on very young or unhealthy animals. There have been experimental efforts made on some less-qualified animals with success, but results are not yet reliable enough to be safe. There is a marked increase in the stress level of any reptile that undergoes any type of injurious situation, including surgery. For this reason, patients are to be healthy, at least young adults, and feeding prior to consideration as a patient.

The two methods that are performed at this facility are adenectomies, and ductectomies. Aden means "gland", duct means "duct", and ectomy means "the removal of".

Adenectomy: Adenectomies are performed mainly on Elapids, although a slightly different method can be used with Viperids, called oral adenectomy, which was also observed on a recent visit to the facility.

- Sterilization

. Tools to be used in the surgeries are instruments regularly seen, such as tweezers, forceps, surgical scissors, scalpel, etc., and they are boiled, then soaked in alcohol between surgeries (Fig. 1) All tabletops and the platform apparatus are covered with a layer of clean newspaper and paper towels, changed with each surgery. Betadine is used to clean and sterilize the area of incision.

- Preparation of the patient

. Healthy unaltered snakes are carefully placed in gallon jars with a few holes punched in particular locations about the lid (Fig. 2). A few drops of Trifluoroethane, an anesthetic, are dropped through a hole in the lid, and the hole is then sealed. The snake remains in this jar and slowly but surely uses up oxygen and the fumes of the anesthetic with it for an average of 15 minutes until sedated.

The actual sedation period depends on the physiology of each individual animal. Once the snake has been removed from the jar, a small "X" is drawn on the specific belly scales under which the heart can be seen beating. Snakes are limp and safely workable for at least 30 minutes, and can be fully revived within 15 minutes to an hour thereafter. The heart rate is monitored throughout the operation, as well as any movement by the patient or unexpected detriment to health at any point. The "apparatus" is essentially the workbench for devenomization.

At this facility, a small platform is fashioned out of modeling clay, and four small arms are used to "strap" patents onto this platform (Fig. 3). They are normally positioned on their back or side, depending on the procedure that is to be performed. Betadine is swabbed over the entire area to be in focus during the session, and all is done with the aid of a large, lighted magnifying glass with an adjustable arm (Fig. 4).

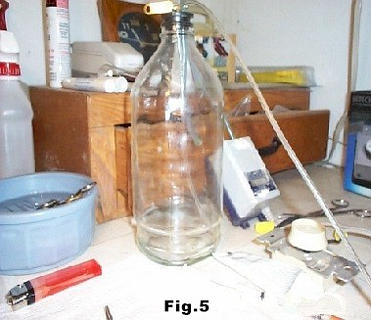

In addition, a small tube is ran into the epiglottis, and anesthetic is pumped continuously with soft air pressure from an aquarium pump connected to a dimmer switch for control, then through a bottle with the anesthetic contained within, and back out to the snake (Fig. 5). This ensures that the patient will not revive during the procedure. The moldable arms on the platform further prevent movement.

†

- Procedure:

With Elapids, the entire venom gland is removed through an incision in the side of the head and the gland completely exposed (Fig. 6).

The gland is carefully separated from surrounding muscle tissue, (Fig. 7), removed from the cavity, and severed at the venom duct. The glands are then placed in a preservative within a small vile (Fig. 8). Q-tips are used to swab excess bleeding from the area during the operation, and sometimes a butane solder-gun is used to cauterize veins if needed to help stop bleeding.

This is a temporary fix and is only used when necessary, and as cauterized tissue will eventually heal, the method seems very effective. The remaining end of the venom duct is also cauterized to encourage proper healing. During the operation while inner tissue is exposed, an injectable antibiotic called Amacacin is supplied to areas surrounding the cavity and about the severed muscle tissue (Fig. 6). It has been determined to be beneficial to also remove a narrow strip of skin from an edge of the incision to minimize the hollow appearance of the sides of the snakeís head once the large glands have been removed. To finish, 6-0 or 7-0 coated Vicryl monofilament apolyorpylene and polyglactin sutures have proven to be most effective to stitch the wound and allow proper healing and absorption. Once the incision has been sealed, a topical triple antibiotic ointment is applied generously to the entire area. It is important to continue to monitor the patient post operatively while the anesthetic wears off to ensure proper recovery. This is accomplished by leaving the snake on a clean surface nearby until it begins to move, or by simply placing it in a container in a quiet and secluded area with ample warmth.

While I was present, a similar operation was performed on a Great Basin rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis lutosis). An oral adenectomy is a procedure that involves removing the venom glands from inside the mouth of a snake to minimize visible scarring. In fact it has been determined that while the safest and most effective procedure to perform on Elapids is the external adenectomy, if an adenectomy is to be used with a Viperid it should be oral. Scarring and detrimental complications and the consequent misshapen contours of the head have prevented experienced operators from commonly performing adenectomies on Viperids at all. Likewise, when glands are removed from the external surfaces of the head on a viper, excessive amounts of tissue must be removed as the glands take up such a large portion of the head. Cobras have much shorter venom ducts, and recovery of venom excretion due to healing is much more possible as a result of a ductectomy, which is why adenectomies are preferred with Elapids.

For the oral adenectomy, the patient is prepared identically to the above, but is positioned in the apparatus on its back. The bottom jaw is propped back with the plastic end piece from the tube anesthetic, and the top jaw is secured flat on the platform with a section of the suture so the top inside of the mouth is fully exposed (Fig. 9).

Incisions are made at the obvious locations of the venom glands, and they are carefully and meticulously separated and severed (Fig. 10). Again, the end of the remaining duct is cauterized, the cavity irrigated with antibiotic, and the wound sutured closed.

The period of recovery thereafter is identical.

4) Full recovery: Full recovery and healing of the incision and tissue may take from one week to a month or two, depending on the time of the last shed prior to the operation, and the physiology of each individual. The snake will usually feed within the first week, but care must be taken to prevent breakage of the sutures. If healing of the wound is not to the point it should be, the animal would be allowed adequate time to heal before food is offered. During the healing period, the animal is maintained in a warm, secluded box or enclosure with either simple furnishings, or preferably no furnishings at all. A bowl of water is available at all times, but the enclosure is kept dry to assist the healing process and prevent infection. The wound is treated with ointment if needed, but most snakes heal quickly and without incident. However, scarring is evident following an adenectomy, and as most Elapids have very large scales in that area, it is impossible to avoid this scarring. Still, it takes close examination to actually notice the operation has occurred. Conversely, oral adenectomies on Viperids of course will show no external scarring whatsoever. But infection is more likely when work has been done in the mouth, albeit still rare- at least at this facility. As another note, any adenectomy patient will be left with fairly obvious "dents" in the head where the glands once resided. There have been experiments with saline inserts that would serve as prosthetic glands simply to fill the cavity in place of the absent venom sacks. These have yet to be proven, and may or may not be effective or accepted by the surrounding tissue. Prosthetic glands are yet to be adopted regularly for these reasons, although I know of one such attempt that has yet to fail.

Ductectomy: This facility has attempted a couple variations of the ductectomy procedure while testing for the most efficient (non-stressful) and effective way to go. Preparation is again identical. While I was there, a ductectomy was performed on a young adult Bitis nasicornis.

- The procedure

: The animal is positioned on its side. Perhaps one of the most skilled activity involved of all the procedures is the meticulous incision made for a ductectomy. A 1/8-inch cut is made below and forward of the eye, almost exactly mid-way between the front of the gland to the tip of the snout. Care is taken to cut between the scales, without damaging any scales, to ensure minimal scarring or evidence at all that an incision has been made at all (Fig. 11).

Once the very small duct has been located and exposed, a section roughly 1/8-inch long is sutured at each end, the severed. One end is severed first and then the section parted from the incision (Fig. 12). Once the connection is cut, both ends of the remaining duct are cauterized, and the incision sutured carefully. An abandoned variation of this procedure was to simply tie off a section of the duct and cauterize the middle without removing any tissue at all.

But this has since proven to be unreliable in its effectiveness, as cauterized tissue tends to heal very well, actually repairing the damaged duct to its original operative state- a dangerous situation indeed.

- Recovery

: The recover of a ductectomy is much quicker and reliable, as much smaller wounds have been made. In fact, because of the method of incision, there is no evidence such an operation has occurred.

†There have been cases of "regeneration", but not as what is readily reported by the general population of hobbyists. Entire venom glands do not regenerate, but enough of the gland may be left behind to allow seepage of modified yet potent venom. Regeneration and healing are entirely different occurrences. Regeneration is the complete regrowth of lost or destroyed parts or organs. Healing is to restore health or soundness to injured tissue, or a cure to an illness. Unintended healing of venom ducts or success of the venom delivery due to an ineffective procedure is not uncommon. I have witnessed such cases first-hand, and needless to say, the people who have made costly mistakes handling so-called "fixed" snakes usually begin treating venomoids with the same respect they would give an unaltered venomous snake. This provides a chance for others to learn from the mistakes of those before them.

Venomoids produced at this facility have quite a track record. Some have been venomoid for around a decade, and some have produced offspring successfully (fully unaltered, perfectly venom-capable offspring of course).

In addition, I have included photos of two venomoid snakes that have recovered fully as venomoid patients. A king cobra (Fig. 13), and a cottonmouth (Fig. 14). Incidentally, the cottonmouth is a 9-year venomoid.

†

Part 3

†Venomoids for sale: A very important consideration is the value being placed on venomoids by the makers and dealers of these snakes, the source from which they enter the market, and the requirements and care once a venomoid arrives in a permanent home.

If one were to buy a venomoid, they should expect to pay at least $100 over the normal price for the same species unaltered. This is a very profitable endeavor for average herp dealers out there looking to supply a thirsty demand. They would pay wholesale prices for an unaltered animal, and pay a fee to the individual that will "fix" the animal (if they can find such an individual). Then they mark that price up accordingly, and end up making more profit on the other end than they would had the animal been unaltered. This would explain the recent flood of venomoid snakes into the market. Incidentally, the herp economy reacts the same way that any other economy does. Supply caters to the demand. Venomoids sell very well, and there seems to be an endless demand for them from all types of keepers. There are many dangers associated with this craze that need to be considered. "Enterprising" individuals may start selling animals that have undergone less friendly "hack-jobs" in order to get their piece of the cake. The same types of dealers may also claim snakes are venomoid without any proof, delivering an unaltered snake for a venomoid price, as it is next to impossible to identify most venomoids by looking at them. The new owner then has a snake that is assumed to be venomoid. This also tests the legitimacy of any "quality" venomoid purchased over the Internet. How does one know itís a healthy venomoid? What is the history of this snake? Who performed the operation? How much experience does this person have performing the operation? What procedure did they perform? Currently, there are no standards of rating sources of venomoids observed by the venomous community, primarily because venomoids have yet to be accepted by the whole of the venomous community. The veterinary portion of the herpetological hobby also does not support the craze while they have yet to embrace venomous hobbyists fully as it is, so it is next to impossible to get a respectable sign-off on the health of such animals anyway. Normally quality dealers back up the health of the animals they sell. Would they also stand behind the health of venomoids? Larger, well-established herp dealers generally shy away from entering the venomoid game for obvious reasons: either they donít support the venomoid movement, or because they have no way of truly backing the health or history of these animals. This does not mean that healthy venomoids arenít available from honest, quality herp dealers, but one may have to search to find a dealer they can trust. But one factor seems positive here: generally, if someone makes a substantial investment in a snake, it is likely appropriate care of that animal will be taken. At least one venomoid maker insists that sales are very common to schools and other educational institutions where animals are used on display. This supports the inclination that the general non-herping public may very well appreciate the idea of "fixed" snakes as opposed to unaltered venomous snakes in the private sector. Of course this is a threatening idea to any purist.

Once a venomoid arrives in a new home, it should be effectively tested immediately. Short of taking the snake to a vet or a lab and having it analyzed in a scientific manner, the laymenís method of testing is far more simplistic, and quite possibly less of a validation than it should be. The idea is to allow the suspected venomoid to bite a live rodent under closely supervised conditions. As soon as the rodent has been bitten, it should be removed immediately for observation, and to prevent injury to the snake. If the animal has been envenomated, it will be obvious, keeping in mind of course that puncture wounds are not harmless to a rodent by any means. There is no more dangerous assumption, than assuming a venomous snake is incapable of injecting venom based on the claim that it is venomoid or devenomized. As mentioned before, a large percentage of venomoid shoppers are out to obtain a venomous species of snake that has been rendered "safe" to free handle, or handle with bare hands. This can be as risky as pointing a gun at oneís self, assuming it isnít loaded based on someone elseís claim. Of course a venomoid can and will bite, and is perfectly capable of sinking fully operational fangs deep into oneís flesh. Also liken this situation to de-clawing a cougar and expecting it not to cause injury in a playful bout of wrestling. Wrestling even the tamest cougar is risky business, as we all know what damage a house cat can do, with or without claws. This illustrates the primary reason it is recommended that a venomoid be treated no differently than if it were an unaltered snakeóit can deliver nasty and very painful puncture wounds. In the case of larger elapids and viperids, there is no reason to be surprised if such a bite damages nerves or leads to serious infection. The secondary and more observed reason to respect a venomoid is that there is no guarantee that any venomoid is truly void of its ability to envenomate.

This also raises another interesting question concerning venomous snakes in general: can a venomous snake be "tamed"? To cite the definition of the word tame, would suggest that an animal is brought from the wilderness into a domesticated or tractable state or has become submissive or docile. While most reptiles are far from being domesticated, none will argue that most non-venomous snakes can be acclimated to human interaction and handling, and often are quite docile. As venomous snakes have such obvious and effective defensive behavior and means, rarely are attempts made to tame them. However, in certain parts of the world, including our backyard, individuals have been quite successful taming venomous snakes to the point of almost trusted interaction. The risk is still there, of course, but success has proven to be quite possible. Venomoids allow a more unique opportunity to study the behavioral variance and capabilities of tolerance of otherwise unapproachable creatures. Without a definite threat of envenomation, efforts to handle and interact with venomous species of snakes increase in frequency if the keeper is so inclined. Some species are more apt to "tame" than others, especially those from the Elapid genera- although even different species within the Elapidea seem to be more responsive to handling than others. Often, once taming has been accomplished these snakes will no longer display any defensive posture or behavior at all, which is much of their allure. As they are not resistant to feeding response, even "tame" snakes will bite their handler by mistake in the event that stimuli are alerted, just as any boa or python would. On the other end of this spectrum are the very nervous and aggressive species and individual snakes that absolutely will not tolerate any interaction at all with human beings. These are the most dangerous of venomous snakes to keep in captivity, and thus are the most dangerous of the venomoids, relatively of course. As there is no standard of placement when these individual snakes are imported and sold, they can end up in the homes or facilities of the inexperienced as easily as they can a skilled keeper. Consequently, at the very least the health of these snakes may suffer as their formidability and ability to intimidate may discourage proper care in their captive environment by all but the most dedicated and experienced of keepers. If venomoid snakes did not exist, this would still be a serious issue, and one that will plague enthusiasts regardless. But, many feel a relieving option may be to devenomize such snakes for the protection of anyone involved, while others simply feel such a snake is a perfect representative of animals that are better left where they belong- in nature.

The husbandry of venomoid snakes seems to be much the same as for any unaltered snake of the same species, save one very important difference: venomoid snakes cannot kill their food and should never be fed live prey. If a devenomized snake were to be either finicky, or otherwise reluctant to eat, allowing a live rodent to explore the cage would no longer be an advantageous method of stimulating a feeding response. They are destined to consume only pre-killed animals, and the thrill of watching a snake hunt a live rodent that has been introduced to the enclosure will not be available with a venomoid.

†

eth∑ic (ethik) n.

- A set of principles of right conduct.

- A theory or a system of moral values: "An ethic of service is at war with a craving for gain" (Gregg Easterbrook).

- ethics.

- ethics.

†

While facts are rarely assembled and presented in a thorough manner in the many debates surrounding the subject of venomoids, what often takes place of them are the more readily available opinions of the participants. Opinions, if they are to be validated at all, must dwell in the interest of ethics and personal preference, not various versions of "facts".

The discussion of ethics is a colorful one indeed, and one without which this paper would be incomplete. Herpetological purists support the belief that captive venomous snakes should remain complete and unaltered, despite the extinct natural lifestyle that once necessitated the need for venom. This is a strong argument, for the very allure of venomous snakes is their uniqueness, and their advanced evolution displayed so readily and effectively. If this is to be observed in a captive environment, every effort is made to encourage the most unadulterated and natural behaviors. It is the aim of a large percentage of enthusiasts to ultimately breed their captives, and to achieve such a success, meticulous and dedicated husbandry is required to stimulate inherent instinct to take place. Any alteration to an animal's anatomy can have a profound effect on the rest of the animal's physiology, and cause a detrimental imbalance. Of course this is quite a trick considering the animal has become destined to a life in captivity as opposed to a life in nature, which is the ecology that produced the animal in the first place. Captive animals fall basically into two categories. Domesticated animals have been reproduced in captivity for so many generations that they would not be able to survive without the care of our species. Captive wild animals are what we call the animals that have been acclimated to a life within a captive environment once given the basic requirements for survival. These animals are the ones we find in zoos and parks, and these animals are often placed in captive breeding programs for the express purpose of conservation of their dwindling numbers. In the herpetological hobby, most herpetoculturists strive to produce captive offspring to either offset the flood of wild-caught animals entering the hobby, or to profit from the obvious marketability of the booming herp trade. Most popular species of reptiles that carry normal genetic traits have been faithfully reproduced in man-made facilities to the point that it is no longer cost-effective to produce them any longer, given that demand for such "bland" variations of these species has reached a plateau in the marketplace. Thus any genetic mutation or aberrance that produces a striking variation in appearance to the old "normal" animals is embraced with frenzied anticipation. Consequently, there are years of trial and error and genetic manipulation, until the right "phase" is finally achieved. Is this an ethical endeavor? Most would say so. Why? Because they are captive animals, and separate in genetic tampering from their natural wild counterpart; in a sense domesticated. These animals now belong to humans, because we have "made" them, or have otherwise achieved ownership of them.

In that line of thinking, is it also ethical to alter the physical anatomy of any captive animal to suit ourselves, given they are now dead to their natural environment and are residents in a man-made captive environment? It would seem so considering the history of human beings and the animals with which we choose to coexist. Physical alteration is an everyday occurrence in our speciesí alternative environment. We have adapted procedures that arguably enhance our lives and the lives of our captive animals as well. While we can ethically change our appearance via plastic surgery, it would be considered unethical to manipulate genetic code to make human babies look like we want them to- as of yet. On the other hand, it has been perfectly acceptable for centuries to reproduce every physical genetic trait imaginable in domestic animals, particularly the canines, gracing us with such abominations to the natural world as teacup poodles, shi-tzus, and Pomeranians. We will crop ears and tails, and have our catís claws surgically removed. We will turn calves born with the equipment to become bulls into much less at a very young age and without anesthesia, and this is a regular and accepted occurrence in the farming community. We will without hesitation have our dogs spayed or neutered to prevent the urge to breed- unless they are of pure genetic ancestry and will produce marketable or competitive offspring- and this is fully supported by groups such as local humane societies, suggesting that it is a truly humane and ethical thing to do. But such alterations are not required for these animals to survive, nor do they have any benefit supporting longevity of the species, often the contrary. If there is benefit to these types of alterations, it is only so within our civilization. If we were to have left these animals alone in the first place, there would be no reason to alter them to fit within our domain. So should it be considered unethical to create a venomoid snakes from a captive venomous snake? By definition of the word "ethics", no. Not by todayís standards does it seem so, and venomoids seem to share a consistency with many examples set by human beings all throughout history.

But ethics are also up to each individual, according to his or her own perception, and oneís ethics and choices of acceptable conduct may differ from another. This is the way I imagine most people would prefer our society to be if they are to retain their own freedom of thought. In the case of venomoid snakes, opinions and ethics will be discussed and displayed as long as the option is available. As always, the proven facts, which are not required, will largely be ignored.

In conclusion, Iím not a scientist or a pro in any way. I am an amateur naturalist and herpetologist and venomous snake keeper. Conclusions I have come to in this article are not solely from my own experimentation, although I have spent quite a few years around venomoid snakes, and predominantly venomous snakes, and consider myself an enthusiastic student of nature and reptile biology. I was hoping to clear the air on many points in the venomoid controversy, without airing any amount of personal opinion. However, some of my personal views may have been peeking from beneath the blanket of observation, so I feel I must review some main points to conclude this paper properly.

Is there any reason to have a venomoid? There are many reasons to have a venomoid, just as there are many reasons to have a gun that shoots blanks. But, most people will not find purpose in a gun that only shoots blanks as opposed to the original design, and likewise, experienced venomous snake keepers will adopt the proper respect and conduct associated with safely keeping and handling unaltered venomous snakes. Such folks have found no reason to own a venomoid. Firing blanks from a gun is valuable to those who need to use guns for training or education, and to those who shoot guns for show and play. So it is with those who are interested in venomoids.

Do we need venomoid snakes? Of course not. It is an attempt to customize a natural occurrence for our own purposes and to fit within a human lifestyle. We also donít need albino boa constrictors, poodles, or Filet-O-Fish sandwiches. But it is in the nature of humans to attempt to improve on our environment and its inhabitants.

Are venomoids worth the price? Venomoids are worth what people will pay, and there is no standard market value set for them. By my observations, there seems to be no price too high that someone wonít pay for a beautiful altered venomous snake, and sometimes it seems truly ridiculous. Purchasing a venomoid over the Internet is risky business, like buying a used car over the phone. A mistake can be expensive in more ways than one.

Are all devenomization procedures effective? They certainly can be, depending on the individual who performs the procedure, their knowledge of snake anatomy, healing, and their skill level. But it is next to impossible to separate the good from the bad, short of seeing an obvious disfiguring hack-job. It is more probable that very few individuals who are currently performing different variations of these procedures are actually skilled enough to achieve consistently effective results and consistently healthy patients, post-operatively speaking.

Is it safe to free-handle a venomoid? Maybe. But that is the most accurate answer to a question that needs a definitive answer before such conduct can be suggested.

Are venomoids truly safe? No. Procedures are not proven, and have a long way to go before they can show to be 100% effective in 100% of snakes altered. Accidents have already happened, and they will continue as long as keepers either handle their venomoids with bare hands, or otherwise fail to show respect for the design of the animal. Given the general intentions of a high percentage of venomoid owners and the lack of any standard for producing fixed snakes, these accidents may become quite frequent and become a serious detriment to the venomous hobby in general.

Can a venomous snake live a captive life without venom? Natural unaltered snakes can, and often do. Many venomoids prove to be just as healthy and long-lived as any unaltered snake, and also prove to grow and breed in addition, just as they are supposed to. But they would never make it in the wild, and they do produce completely potent unaltered offspring. Additionally, there is no way to tell how well a particular snake will live after devenomization, and much study is needed from the scientific community. Given that the scientific community most often shuns the subject of venomoid snakes, it may be a while before we see much concrete data. I suppose I should go back to school. Also, venomoids require special care, and should be considered handicapped if kept by experienced keepers of unaltered snakes. Either way, venomoid snakes do deserve proper care despite their handicap.

Should venomoids be a legitimate option to the general public? Maybe there are situations where a venomoid would be a considered a legitimate option by the herp community. But for now, it is legitimate only as an option of free will within the community. I believe the option should be there because I believe freedom should be preserved at all costs, but it is not a necessary part of the herpetological community, any more than leucistic leopard geckos are important to the preservation of leopard geckos to gecko enthusiasts. The legitimacy of venomoids will be in question for a long time, and it should be. If it is to be accepted, there are many important standards to set, especially in procedures and dealing methods. One thing for sure, is that when the idea of a venomous snake rendered venom-less is brought before a member of the non-herping general public, it is most surely embraced without hesitation as a great idea indeed. If the integrity of proper venomous reptile keeping is to be preserved at all, discussion and study of the venomoid issue should be addressed seriously and soon.

Is creating venomoids an ethical practice? By general human standards, I believe it is consistent with many accepted practices in our civilization, and fits the definition of ethical. But on a personal level, it is up to each individual to explore his or her feelings on the matter, and allow others to do the same. For example, I personally donít like the idea of de-clawing cats, and I would never have it done to any of my cats. The mere fact that we have taken venomous snakes from the wild and placed them in cages means that we have forfeited our observance of their right to live a natural existence. If that is ethical, than anything else we could dream up in captivity would probably pass in at least some circlesóand does.

This paper has been written from the point of view of an amateur, but I have tried to be as thorough as possible. I imagine I will receive argument from both sides of this controversy, so I must say that this should not be taken as an end-all overview of the venomoid scene. I meant to provide an overview, and fuel for discussion. If I manage to cause further debate and study, then I have achieved success.

†

Special thanks to Richard Richey and Tim Friede for sharing their knowledge and expertise.

Without the assistance of these two, this article may have been possible, but may also have been shorter and completed on time. Iíd also like to thank Jaffo for the photography and Brett for the camera, and Ms. Grammar for, well, you know.

Jeff Miller is a wannabe naturalist, adventurer, and amateur herpetologist from Oregon who has several years of experience keeping reptiles of all kinds, including many species of venomous snakes. He also happens to have a couple of venomoids.

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by KingCobraFan on March 29, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

First of all, I'll preface this comment by saying

that I've never handled a venomous snake, but have

been fascinated by them since childhood. I felt Jeff

Miller's article on venomoids was excellent in that it

explored both sides of the issue. My opinion is this:

I can see no reason whatsoever to own a venomoid. For

education, there's literature and video. As far as I'm

concerned, if you're going to alter a snake in this

manner, it should just as soon be left in the wild. To

me, a venomoid is akin to having a Ferrari with no

engine in it.

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by Squamatau on March 30, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Great article Jeff!! I personally am of the opinion that keeping a venomoid snake is like keeping a gun that can't fire bullets. I'm still NOT gonna play russian roulette with that gun. But a well presented interesting article for sure!!! Great work!

|

| |

|

RE: Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by Gnochman on April 21, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

In essence this is purely a moral/ethical issue here. It boils down to humans trying to dominate, encapsulate, and "domesticate" nature. Its just how far will you go? However, we also see tinges of "machismo" here particularly as evidenced by the line "keeping a venomoid snake is like having a Ferrari with no engine." Can't be cool if there is someone else out there that may think you got a venomoid snake, or just the frame of a ferrari. Me, I'm gonna hold on to my Pontiac Fiero (Rosy Boa), and I'll wait and see if during my mid-life crisis I have the urge to purchase the body of a lotus (venomoid crot.) or a Lambourghini Diablo (full venom D. A. Polylepis).

: )

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by vettesherps on July 2, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Just for the record, I am not against venomoids, but what I am looking at appears to be a total mutilation. I also am convinced that at in at least one instance shown in this article there is an almost absolute case of the animal still being venomous. I have witnessed this surgery done by an expert and it was performed under sanitary conditions and with the proper tools and anestia. The surgery was performed by making a very small incision and both the primary and secondary glands removed. When done properly there is no need to remove skin to eliminate the hollow look. I am appalled the pictures presented in this article and can only think it will not help the cause of those individuals who are in favor of venomoids. I agree in principal with what you ar edoing Jeff but do not like what I am seeing in this article. Sorry, but that is my opinion.

vettesherps

|

| |

|

RE: Venomoids: An Overview (correction)

|

Reply

|

|

by vettesherps on July 8, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

|

Sorry I need to correct a statement in my earlier post. The primary glands were not removed. They were simply made non-effective by ductal ligation. Sorry don't want to misinform anyone.

|

| |

|

RE: Venomoids: An Overview (correction)

|

Reply

|

|

by vettesherps on July 8, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

|

Sorry but the previous post contained an error. The primany glands are not removed simply ligated. Don't want to misinform anyone.

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by TMB on October 10, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

|

I would like to thank you for presenting a fairly through account of what venomoids are, but wish to add somethings, first of all there are two ways of rendering a venomous snake a venomoid, first is by ligating the venom ducts, second is by doing a complete adenectomy[total removing the gland], the latter was pioneered over twenty five years ago by a DVM, and is documented in several Veterinarian Medicine Magazines and book of that time. This surgery renders the animal venomless, where as Ligating the ducts does leave room for reversal, plus over the years we have learned that some venomous snakes actually have some degree of toxicity in their saliva, one of these is the Sri Lankian Naja naja. We have found that this one type of Naja naja's saliva will over a period of 1 hour kill a mouse but does do so with a rat, should a human recieve a bite of this type there will be different symptoms such as nausea, headahce, flush warm feeling thru out the body and in some cases mild euphoria, with these syptoms lasting from 20 minutes up to 4 hours in cases we have noted . Bit after doing these surgeries for over 25 years we have yet to have a reveral in any animal recivieing a adenectomy, and some our animals are 20 plus years post surgery so would seem to work. But of course it just is not everybodies cup pf tea.

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by Dave_the_herp_handler on January 5, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

I don't think that cutting open a snake just so that someone can keep it in his\her room is a very humane thing to do. I mean come on, if you want to keep a snake then you should be able to pay the price. It didnt want to live with you, you made it. You picked the snake, so you should have to live with it being venomous. If you dont want a snake that can bite you and send you to the ER, then go to your back yard, maybe you can find a nice Garter Snake.

"If you can't stand the Venom, then don't pick up the snake."

- David Yardley (Inspired by Harry S. Truman)

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by Timber_Rattlesnake on February 17, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Earlier I voted yes for the venomoids without thinking, and I wish I didn't now that I read more about it.

Why have a venomous snake if its not goin to be venomous only to impress your freinds or whatever to get a response as...SO COOL! How dum!

If you get a venenmous snake I suspect you to pay the price.

If you only want a venomoid then dont get a "venomous snake" admire them where they really belong...out in the wild.

Because the venom is what makes a venomous snake a venomous snake.

It also serves as help in digesting their prey.

I only believe in venomoids for teaching the audince where a close area is a must.

So why get a venomous snake if your not gonna pay the price.

For people who have them I have no respect for them as a true herpetologist, except as for the above cause.

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by ferretworks on July 8, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

First of all: Hats off to the article. A truely un-biased look at a subject loaded with controversy.

I will also start off by saying I own a Venomoid West African Gaboon Viper. This particular snake was surgically altered by the "Ductectomy" method without a trace of scarring or mutilation. The snake was taught to eat pre-killed, and did so for a period of over 2 years before the surgery was performed. The surgery was also only performed when the snake was in a completely healthy state. In doing the surgery, a fair amount of the duct was removed as to aid in the insuring of no regrowth (In other words, No-Hack Job). I will be milking the snake in the future on a nearly-year basis to ensure that venom is not present.

I honestly believe that you can not compare hot snakes to cars. No comparison. I mean, the Ferrari with no engine? Whats that? Is the snake still not intrigueing and beautiful? You can say that the Ferrari shell is still beautiful, but when it comes down to it: My snake still acts like an ordinary gabby. Only I feed it pre-killed, a practice that should be preformed for all captive snakes in the FIRST PLACE! I also believe the Gun with no bullets is an in-accurate statement (At least for a snake that has had a Ductectomy operation). I believe a more accurate statement would be a gun with a trigger lock on it... a more or less permanent trigger lock.

With that being said, why would a person place a trigger lock on a gun? To protect themselves from the gun? No! To protect their loved ones. I know how to handle the snake. But if by some small chance, it were to fall into the hands of someone else...

With my luck, a burglar would break into my house, knock over my snakes cage, get bitten, lose all functionality on his/her right side of his/her body, get Johnny Cochran for a lawyer and sue me for over $2 million in punitive damages.

I treat my snake as if it were fully equipped and ready to kill. In fact, I have the phrase "repentinus obitus" on its cage which means "Sudden Death" in Latin. I am also very protective of my snake, not allowing anyone to handle it. When I mean handle it, I am referring to removing it from the cage to soak or clean the cage (Not playing with it at a drinking party or "trying to impress friends" as some have stated). I do have some peace of mind though that if it were to tag someone, that the good lord would be in that persons favor rather then against.

I know some of you are already saying "Well, if you can't keep it away from other people, then you shouldn't have it." I am not saying that I can not keep it away from other people. I can do that very well as a matter of fact. But there is no telling what the future may bring. I mean, look at all of the precautions people take with swimming pools, and yet how many children drown each year. Look at all the regulations OSHA has in place for the workplace, and yet deaths occur in factories everyday. In all cases, their was bad judgement and mismanagement usually. So, when OSHA comes in what do they do? They look at ways to prevent such accidents from happening by stricter regulations and rules and laws and etc.

By myself owning such a snake, I may not be considered "A True herpetologist" by many. Want to know how I feel about that? I feel just fine. If it is such an elite group, then I guess I don't want to be a part of it. But I very much admire and respect my snake.

Respectivly,

ferretworks

ferretworks@yahoo.com

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by osirushamburger on September 28, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

i think it all sounds great!

anyone who is offended by this is R-E-T-A-R-T-E-D

i say.. if this defies yer ideas or "code of honor" or some bullshit..

then dont read it.

i found it all very informative, whether or not i use

this information is yet to be decided..

but any truthfull information, is good information

thx for yer time

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

Anonymous post on November 24, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

I'm not going to argue about the ethical question of whether or not snakes should be rendered "venomoid", I just think people should think hard about the way the procedure is performed.

The previously described anesthetic protocol and technique may be ultimately effective in most cases, but is decidedly barbaric compared to the current standards of veterinary medicine. The snakes are anesthetized with dry cleaning solvent (which is relatively non-toxic, but can be a hazard to ALL exposed), non-sterile technique is used to perform the surgery, and no effort is made to manage pain in these animals.

The argument about whether it's right or wrong to perform the surgery falls into the same category as those about de-clawing cats, docking dogs' tails and ears, etc. You will never have agreement from all parties...but most will agree that IF surgery is performed, appropriate techniques should be used and pain should be managed.

There are veterinarians who do perform this procedure. The cost may be more, but you get what you pay for. And remember, it is illegal for a person without a veterinary license to perform surgery on an animal that they do not own.

I don't mean these comments to be inflammatory. Everyone has to make their own choices according to individual sensibilities. I just encourage people to make educated decisions.

|

| |

|

RE: Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by Gnochman on March 11, 2003

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

An additional thought re: venomoids. How is it not relatively cruel to keep one or several of your herps in a Rubbermaid container that is only 3-6 inches tall stacked in a rack for the rest of its breeding life? One may say that the snake is not cognizant of their confinement, yet we don't know for sure. One might also assume that the venomoid snake is not cognizant (at least after it has recovered fully from the surgery) that it is now a venomoid. So if there are indeed no significant deleterious effects of removing the glands (i.e. affecting the quality of life or life span), then how is it any less cruel to confine them in small dwellings for the purpose of breeding convenience?

Stop the Madness : )

JOn

|

| |

|

Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by jay72 on April 15, 2003

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

|

I think that the whole venomoid practice is a disgrace to our hobby. It will bring the wrong kind of people into the hobby. To put these snakes through this procedure is an atrocity. If these people who choose to keep venemoids really cared about the snakes and not their own image they would be against this stressful and inhumane procedure. The fact is that there are alot of snakes that dont even survive the procedure and there is no way of knowing how much pain the snake is going through after the procedure. If people are really interested in venomous snakes, they should dedicate the time and effort in understanding husbandry and handling of these fascinating animals.

|

| |

|

RE: Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by CFoley on June 1, 2003

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

I personally am against Venomoids. Im just about keeping things natural, I also like non venomous. Id rather purchase a non venomous animal than pay money to have one "mutilated." I guess each side has its rightful argument, but this is just my opinion of it.

As far as everyone taking about how keeping venomoids makes you not "herpetologist"...Im going to steal a quote from someone, its from Seamus Haley, who i believe stole it from Ken Foose. "A young boy with a frog in a jar is a herpetologist"

The word herpetologist meaning: one who studies reptiles.

|

| |

|

RE: Venomoids: An Overview

|

Reply

|

|

by Msurinamensis on June 16, 2003

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Oddly enough I ran across this article while googling Ken's name in a search for some of his slightly older writings about gender determination in varanids and was just a bit suprised to see my name come up...

I did in fact steal the quote from Ken Foose, it's something he said to me once when I was being... less than respectful... to someone online and utilizing their lack of an educational background (formal or informal) to belittle them. The term "herpetologist" is literally "One who studies herpetology" but the phrasing really made me take a few steps back, disentangle myself from the argument I was involved in and refresh my views about the value any given individual might bring to the hobby/science/industry regardless of their educational background... heck, some of the greatest contributions and best reccognized names are those who never attended college or even, in some instances, graduated high school.

I needed to be verbally kicked in the head by someone who knew better before I saw it myself... but being a "herpetologist" has nothing to do with education or background or what breeding accomplishments someone has under their belt, it's a term that can be applied to anyone who observes a herp and forms a conclusion, the conclusion doesn't even have to be correct.

Since I do have strong feelings about the venomoid issue though, and I did just register to post on a website I have perused for years, I may as well voice it.

As a personal matter, I am against the production of or encouragement of the production of, venomoid animals.

There hasn't been signifigant enough evidence compiled to prove that the procedure is reliable for the intended goal of cessation of venom production.

There hasn't been signifigant enough evidence compiled to demonstrate that the procedue falls within acceptable risks to the animal during the surgery itself and in the recupperation period afterwards.

There hasn't been signifigant data collection about the importance of venom as a digestive aid and, contrary to the presentation in the above article (which was otherwise very well thought out and well written) the evidence that has been collected suggests very stongly that the venom is quite important... the more toxic the species, the more important it becomes... Studies can be skewed in either direction based on the toxicity of the species used for the study itself, a cottonmouth has not evolved the same level of potency or venom yeild as an EDB, the digestive system and metabolic processes have not evolved to utilize the more efficient digestion... The logical conclusion to this is that the more potent the venom for any given species, the more reliant they are on the venom as a digestive aid and the greater the potential health impact if their abilities in those regards are removed.

The biggest issue I have with the procedure outside of the potential health effects on the snake and my own tendency to shy away from anything that deviates from the natural "purity to the greatest extent possible" of the animals i personally choose to keep is the complacency that is all too often developed with venomoid animals.

Ignoring for a moment the discussions about the macho factors involved with keeping the species to begin with, I ask anyone reading this if they really treat every snake they encounter in an identical manner... I know I personally am far more complacent when handling a small non-venomous colubrid than when handling even a six or eight foot boid and am far more complacent when handling a boid then when handling any hot... Can people honestly say that they would NEVER become careless with these venomoid animals, even knowing that there is a potential, however slight, for venom production even after the surgery?

There are a couple more quotes by Ken that I repeat often and loudly because they ring true with what I personally believe... "There are two kinds of hot keepers, those who have been bitten and those who will be." a phrase repeated so often that the originator is unknown, but I first heard it from Mr. Foose. I keep a few hots myself, nothing too impressive and nothing amazing or unusual but I keep them with the understanding that they have abilities that I need to be prepared for and respect. This understanding is what makes me a responsible keeper, I take every precaution, never handle when not needed for maintenence, never freehandle and keep the animals in locked enclosures that can be divided from the outside. I keep emergency numbers on speed dial and maintain a cell phone exclusively for the purpose of calling those numbers should the need arise. If I didn't have the respect I do for the potential these animals have, I might not take such precautions and might end up paying an unpleasant price.

What's worse... any case of envenomation usually makes at least the local news if reported, this would likely be doubly true for a case where the animal was believed to be venomoid, the last thing our hobby needs is that foot in the door public opinion to provide a toe-hold for rabid anti-human animal rights groups by allowing situations like that to occur.

The second quote I wanted to mention that, once again, I personally first heard from Ken (I do have a habit of pestering him whenever possible, he's a man I have an overwhelming respect for, even after having learned that he was a KC Chief's fan) is "The most dangerous snake in the world is the one in front of you right now." This just goes a bit further to illustrate the need to have a respect for the individual capabilities of any animal you might be handling, a respect that I have seen the owners of venomoids lose all too often as they assume the animals in their care have lost these abilities.