Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

from

Dean Ripa

Website:

www.bushmastersonline.com

on

August 2, 2001

View comments about this article!

Why my bushmasters won't strike my artificial arm, and other sundries of the heat strike

By Dean Ripa

The thermal (infrared) sensory abilities of many snake species are well known (e.g., Noble and Schmidt, 1937; Bullock and Cowles, 1952; Barrett et al., 1970, &c.,). Extraordinarily sensitive, the "heat pits" of snakes can sense temperature changes, perhaps as little as 0.003 degrees Celsius. They help locate prey, guide the predatory strike, and are even used as anti-predator devices (Greene, 1988, posits this as their evolutionary origin). Bushmasters (Genus: Lachesis Daudin, 1803) use their infrared receptors almost exclusively in striking (conversely, they rely greatly on vision in courting and male-male combating; Ripa, 1999; Ripa 2001). When confronted with an edible but non-moving target (e.g., a rodent too scared to move), bushmasters sometimes "bob" their heads rapidly in order to thermally "sight" the prey (Ripa, 2001). This lends credence to the idea of Crotaline pits being a kind of imaging device rather than simple thermal receptors: the prey object (or else the receptor itself) must "move" or the object cannot be accurately targeted.

One of the problems of manufacturing the antivenom for bushmaster bite has been to obtain "good, healthy" venom from snakes that typically die rapidly in captivity once subjected to the stress of venom extraction; e.g., Bolaños, (1972) noted that venom yield fell from 233 mg to 64 mg after the "milked" snakes had remained in captivity. If venom yield is affected by the method of extraction, it is probable that toxicity of venom would be affected as well. Hence, the venom of roughly handled snakes (in snakes sensitive to stress) may produce less potent venoms than their healthier counterparts, and not reflect a true picture of normal venom. Such contingencies may further amplify the disparity described by Hardy and Haad (1998) of the low laboratory toxicity of bushmasters vis-à-vis high mortality in persons bitten. The venom collected by conventional methods in the laboratory may be as constitutionally "unhealthy" as the captive, which could well affect the quality of antiserum.

Capitalizing on the propensity of bushmasters to "heat strike first, ask questions later," I have devised a non-harmful method of extracting their venom. A dog’s rubber play-toy, with a soft, thin, rubber exterior and hollow interior (a "football" shape proved serviceable), is heated to approximately 40–50° C and offered to hungry bushmasters who strike-hold the item exactly as if it were a prey animal. The venom is expelled into the hollow interior of the toy and can later be extracted by cutting it open. Because the bushmaster’s tendency is to hold on tighter and inject more venom when resistance is offered, one can manually induce greater venom yield by manipulating the object, and/or "safely" (I use this word gingerly) reach in and massage the glands of the snake (causing more venom to be expelled) without its releasing its bite-grip on the rubber toy. One does not need fear the snake swallowing the object for once it is released for re-positioning, chemical cues will inform the snake it is not prey and it will then abandon it. Using this method I have extracted venom equal to the greatest yields ever recorded for bushmasters (over 330 mg). This method is excellent because it does not stress or injure the snake, as does the conventional method of seizing it behind the head and "milking it". Strike induced chemosensory searching behavior (involving strike-release) has been described for Old and New World vipers (Chiszar et al., 1982) and strike-hold tactics have been described for others, including jumping vipers (Atropoides nummifer; Chiszar and Radcliffe, 1989) and bushmasters (Chiszar et al., 1989). Ripa (1999) reported that bushmasters do not require chemical cues, only heat, to provoke strike-hold, and suggests that a distinction be made between the forms of strike-hold behavior. These may be divided into two kinds: Chemosensory-Visual Induced Strike-Hold (CVISH), such as can be seen in many Old World viperids, especially the Bitis group, as well as many New World pitvipers; and another type, Heat Induced Strike Hold (HISH), as employed by bushmasters. These types may occur in concord (and most often do where endothermic prey is taken), but are by no means obligatory to one other. In the former, CVISH, chemical clues qualify the object as prey, and the strike is guided visually to its target. Snakes that regularly feed on ectothermic prey employ this type (e.g., Bothrops), although they are not confined to it. In the bushmaster, which eats only endothermic prey, chemical clues doubtless play a significant part in locating the hunting site, and determining presence of prey; however thermal cueing alone is the final requisite to induce the strike. Chemical clues (and chemosensory searching behavior) may be required only after the fact—that is, after the prey has been subdued or killed—in order to relocate the dropped prey when it is to be repositioned in the mouth for swallowing, or to trail it for short distances if strike-hold has failed. Note that the bushmaster will not swallow the rubber ball, although strike-hold it, if it is warm. However, the bushmaster will rarely strike-hold a cold dead rodent (one at ambient temperature or below), but will strike-hold a warm one. The feeding episode rarely occurs in the absence of an initial strike sequence (which is not to say that bushmasters cannot be made accustomed to eating cold dead prey in captivity; however, they will rarely strike it per se, except in a defense mode).

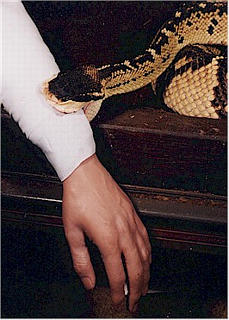

Bite on a prosthetic arm, heated to approximately 100° F to induce strike-hold. The snake would not strike the object unless warmed, regardless of artificially scenting it with rodent odors. The bushmaster's strike is thermally cued, suggesting that insulating materials (e.g., rubber boots) might be sufficient to prevent most bites occurring on those portions of the anatomy that are sufficiently covered.

Copyright 2001 Dean Ripa

Granted, a greater incidence of strike-holding the rubber ball can be provoked in bushmasters by providing prey-scent in the form of rodents kept caged nearby (and this may be necessary with certain specimens); what is significant is that prey-scent is not necessary in most cases. (Note: these experiments work only with well-acclimated, feeding specimens; obviously a snake that cannot be induced to feed at all will not strike-hold the rubber ball, rather it will strike-release it in the typical defense strategy and very little venom will be obtained). HISH in bushmasters has occurred in bites on human beings as well. Mole (1924) tells of a bushmaster bite on the Hon. Albert B. Carr of Trinidad in 1898.

From Hardy and Haad (1998), ". . .Carr reached into the burrow of a ‘Lappe’ (Rodentia: Agouti paca) and felt a sharp stab and upon withdrawing his hand saw the head of a large ‘Mapepire Z’Ananna’ (L. m. muta) holding onto his thumb." Was the Hon. Carr mistaken for prey? Evidently he was, if the above sequence is accurately portrayed. The fact of the man "withdrawing his hand" and seeing the snake "holding onto his thumb" suggests a strike-hold response; in a strike-release bite, he would not have seen the head that bit him until after the fact.

This is typical of the "bite first, ask questions later" food-getting strategy of bushmasters. Any warm blooded prey is a candidate to become a food item, and any warm object is a candidate to be strike-held. Your reporter, who has the dubious distinction of being "the most bushmaster-bitten person in history," has four times been envenomated by bushmasters, and twice strike-held on account of predatory HISH. A third strike-hold (involving a very angry neonate that was being medicated), was a defense response, suggesting that when a bushmaster gets mad enough it can get confused as to the proper hold to use!

Shining a light into the heat-pits of these snakes provokes the Strike aspect of the HISH response. Persons walking with a flashlight through jungle at night can be in for a startling experience, if a bushmaster is lying close-by. In a mild sequence, the snake merely raises its head up to considerable height in order to investigate the unusual phenomenon. But when the light is very bright, sudden and close-by, the startled snake attacks the light frenziedly, hurling itself at the "hot" object in a series of maddened, rapid strikes, one after another. This can be disconcerting in a snake that can strike four feet high! The strikes may be so violent as to propel the snake’s entire body toward the intruder. The sudden appearance of heat appears to cause of sort of sensory overload, and the snake literally goes berserk. Native hunters who had been searching for small game at night using various kinds of torch lights (electric, carbon, gas, etc.) have told me tales of bushmasters "rising up out of nowhere" to strike light out of their hands (after which the terrified hunters fled the scene, abandoning the torch light behind them). The sudden ignition of a match flame can have the same effect, as smokers visiting my facility have observed when an alarmed bushmaster (demonstrating the possible health hazards of cigarettes), made an unexpected lunge to bite them in the face—the glass front of the enclosure, however, protecting them from harm.

Native tales of bushmasters being attracted to fires built in the jungle probably have a factual basis; if a bushmaster were nearby when the fire was being built, one could almost expect it to come over to investigate. In my travels I was intrigued at the extreme caution with which some native persons approached the task of building a cook-fire while we were hunting bushmasters in remote areas at night.

Recent attempts to quantify defensive behavior of venomous snakes have been made. Dorcas (1999) tests the behavior of 50 free-ranging cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) when confronted by a human antagonist. The cottonmouths encountered in the field received one or more of three treatments: (1) one of the scientists stepped beside the snake with his boot touching the snake's body and held that position for 20 seconds; (2) one the scientists stepped directly on one of the coils of the snake for 20 seconds with enough force to cause discomfort to the snake; or (3) one of them grabbed the snake at midbody with a set of snake tongs modified to resemble a human hand or arm. The behavior of the tested snakes (e.g., tongue flicking, crawling away, gaping, musking, striking, biting) was recorded during each stimulus. When stepped beside, about 50 percent attempted to escape, about 25 percent gaped and none struck. When stepped on, about 50 percent gaped, and only 10 percent bit the boot. When grabbed with the artificial hand, about 35 percent bit.

The obvious flaw with this study (and others like them that have appeared) is that the bite-subject (the boot, the fake hand) is not a real human foot, or a real human hand—that is, these object do not radiate warmth. The thermally cued snakes do not bite these objects because they are of neutral temperature. They do not bite them for much the same reason they do not bite each other, while they will bite a rodent that walks on top of one, or a man that sits on one, or a real hand placed firmly upon one. Of course, gross generalizations about the response cues of snakes will always be hazardous, for those responses vary from species to species, and even intraspecifically. Some species will bite the "cold" boot or fake hand more often than others, because they rely on visual cues to a degree greater than other species. Others, like bushmasters, will rarely bite anything (even in a defense strike) unless it is warm. For example, if I were to repeat the Dorcas (1999) studies with my bushmasters I have no doubt that no-strike/no-bite incidences would occur almost 100 percent of the time. This would not prove that bushmasters are not easily provoked or will not defend themselves—it would only prove that they didn't like to bite cold blooded (or cold bodied) objects. If the Dorcas (1999) studies were repeated with warm-bodied objects instead of neutral objects, the outcome would be vastly different.

The other flaw in studies of this sort is that a startled snake behaves very differently from one that has been accustomed to human manipulations. Snakes are not mechanical puppets that produce strikes to order. A snake that can be goaded into striking the first time, or the second, will often cease striking altogether unless left alone for a while and then brought out again later when it is "fresh". Snakes evidently know when they are being legitimately threatened and frequent handling "tames" them to such an extent that they might not strike at all.

Few can deny that some of the most "vicious" snakes on earth belong to the genus Bothrops. And yet recently a Costa Rican herpetologist-friend of mine "trained" a terciopelo (Bothrops asper) not to strike. To do this he simply took the snake out of its cage everyday and put it through a series of repetitious exercises that involved walking up to the snake and placing his foot upon its back. The snake soon learned not to strike his foot (which was covered with only a thin leather shoe) or leg, which was covered only by a sock and pants (e.g., heat was present). Whether the snake actually "learned", or simply became numbed to such manipulations (a stress condition usually ending in death for the snake), remains to be seen, but the fact remained that it ceased trying to bite its keeper.

In another instance, again involving a terciopelo, a manufacturer wished to test and film the efficiency of their line of snakebite-proof boots. For this task, herpetologist Matt Harris (pers. com) supplied them a particularly nervous (and easily aroused) Bothrops asper. In only one instance could they provoke the snake to bite the boot (when the cameras weren’t rolling), and their test ended in failure. This test says nothing about the defense reactions of Bothrops species, or any other snake, to being stepped on by human beings. But it does say a great deal about the discretion snakes use toward the objects they bite, their quick habituation to these objects so that they soon learn not to bite them, and the effectiveness of insulating materials that isolate warmth behind a surface. The boots did not really need to be "snakebite proof" to be effective, their neutral surface temperature, among other factors, simply prevented the bite from occurring.

Literature cited

Barrett, R., Maderson, P. F. A., and Meszler, R. M. 1970. The pit organs of snakes. In Gans, C., and Parsons, T. S. (eds.): Biology of the Reptilia, New York, Academic Press, 1970.

Bolaños, R. 1972. Toxicity of Costa Rican snake venoms for the white mouse. Amer. Jour. Trop. Med. Hyg. 21:360-363.

Bullock, T. H., and Cowles, R. B. 1952. Physiology of an infrared receptor: The facial pit of pit vipers. Science, 115:541.

Chiszar, D. C., C. Andren, G. Nilson, B. O’Connell, J. S. Mestas, Jr., and H. M. Smith. 1982. Strike-induced chemosensory searching in Old World vipers and New World vipers.

Chiszar, D., J. B. Murphy, C. W. Radcliffe and H. M. Smith. 1989. Bushmaster (Lachesis muta) predatory behavior at Dallas Zoo and San Diego Zoo. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 27:459-461.

Chiszar, D., and C. W. Radcliffe. 1989. The predatory strike of the jumping viper (Porthidium nummifer). Copeia 1989(4):1037-1039.

Dorcas, M. E. 1999. A study of the defense behavior of cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) in South Carolina. N.C. Herp. Soc. Newsletter No. 22:2

Greene, H. W. 1988. Antipredator mechanisms in reptiles. In: Biology of the Reptilia, vol. 16, Ecology B: Defense and Life History, ed. C. Gans and R. B. Huey, 1-152. New York: Alan R. Liss.

Hardy, D. L., Sr., and J. J. S. Haad. 1998. A review of venom toxinology and epidemiology of envenoming of the bushmaster (Lachesis) with report of a fatal bite. Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 33(6):113-123.

Mole, R. R. 1924. The Trinidad Snakes. Proc. Zool. Soc. London 1924:235-278.

Murphy, J. C., and R. W. Henderson. 1997. Malabar, Florida; Krieger Pub. Co.

Noble, G. K. and Schmidt, A. 1937. The structure and function of the facial and labial scales of snakes. Proc. Am. Phil. Soc., 77:263.

Ripa, D. 1999. Keys to understanding the bushmasters (Genus Lachesis Daudin, 1803). Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 34(3): 45-92, 1999.

Ripa, D. 2001. The bushmasters (Genus Lachesis Daudin, 1803); Morphology, Evolution and Behavior. Wilmington, N.C.: Ecologica

Dean Ripa has collected snakes in 35 countries. In 1994 he was the first person in the world to breed two species of bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys and Lachesis melanocephala), the first to record their reproductive rituals and many other behavioral habits. He is the author of the up-coming book, "The Bushmasters (Genus Lachesis); Morphology,Evolution and Behavior."

|

RE: Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

|

Reply

|

|

by Charper on August 2, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

He didn't. He just owns one to use for these types of studies. The last time I saw him, he had 2 arms. ;-)

CH

|

| |

|

RE: Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

|

Reply

|

|

by Charper on August 2, 2001

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Something I've noticed as well.... "Some", but not all of the Eastern Diamondbacks I've owned seem to be thermally cued to strike as well. If a dead rat is not heated up, they won't strike it.

Others just seem to be so temperamental that they'll strike anything that moves. These are generally all wild caught adults though.

CH

|

| |

|

RE: Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

|

Reply

|

|

by coopy on June 18, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Hey

I loved reading your article.

I am fascinated with Bushmasters

My in-laws live in Trinidad. I have been there three times.

I spent many days searching the forests down there but

did not have any luck finding a bushmaster.

I read a great book while in College titled "Snake Hunter's Holiday" Found it in a library by accident.It is a very old book. Ever heard of it?? The book is about two herpetologists who go to Trinidad searching for a Bushmaster. You would love it. If you are able to find it anywhere let me know.

|

| |

|

Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

|

Reply

|

|

by hotserpents9602 on October 8, 2002

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Hey just wana say that, that was a great article.

And Dean Ripa your Serpentarium is AWESOME, takes me about three hours to get there but its worth it.

Eddie

|

| |

|

RE: Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

|

Reply

|

|

by melindaLouise on October 11, 2004

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

I live where the Serpenterium is located but I've wondered why he choose Wilmington for a place like this? If anybody knows let me know

|

| |

|

Bushmasters and the Heat Strike

|

Reply

|

|

by BamaLen on December 13, 2013

|

Mail this to a friend!

|

Dean Ripa is a WILD MAN!! =)

The dude is a Bushmaster god!!!

Rock on Dean!

"She's sitting there, looking at me with this sly smile, saying, 'I've just killed you, now what are you going to do?'" This after he had been nailed for the 7th time by one of his Bushmasters! A wild man, I tell ya!!

Len

|

| |

|

Email Subscription

You are not subscribed to discussions on this article.

Subscribe!

My Subscriptions

Subscriptions Help

Other Field Notes Articles

The Spring Egress: Moments with Georgia’s Denning Horridus

The Spring Egress: Moments with Georgia’s Denning Horridus

|